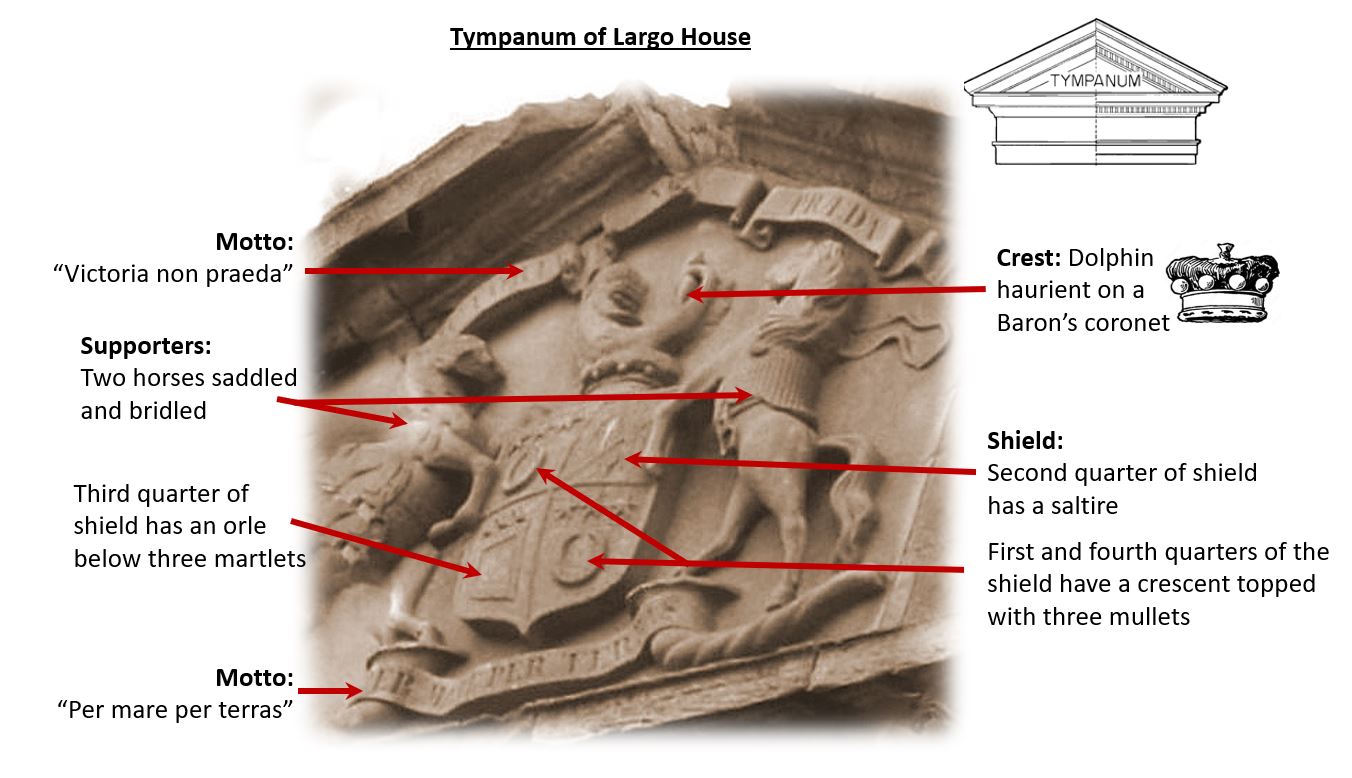

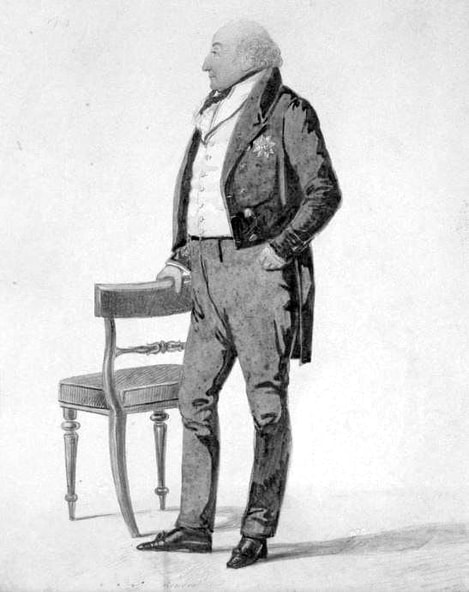

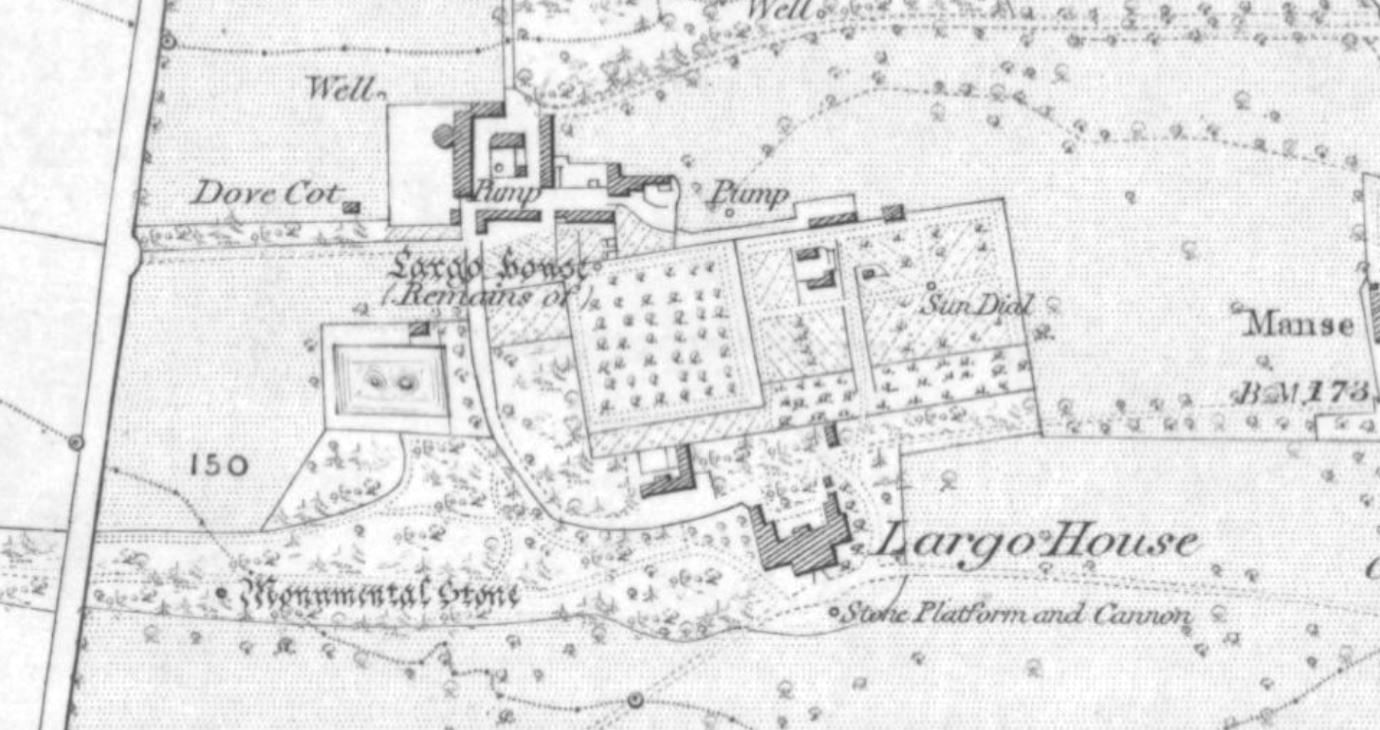

The previous post looked at the life of General James Durham (1754-1840) and noted that one of the changes he made to Largo House was the addition of a coat of arms on the tympanum above the central upper windows. 'Coat of arms' is the popular term for what is more accurately a 'full heraldic achievement'. This post attempts to 'read' the heraldic achievement displayed on Largo House and understand the significance of the various elements of it. The component parts of the full heraldic achievement, including the shield, supporters, crest, and mottoes, will be described.

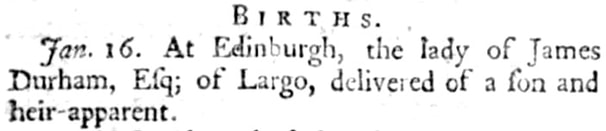

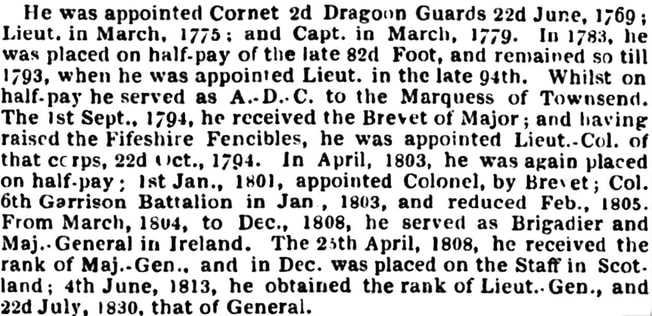

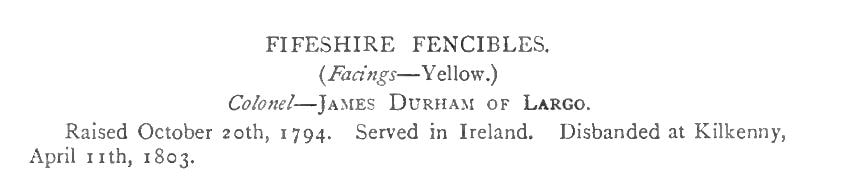

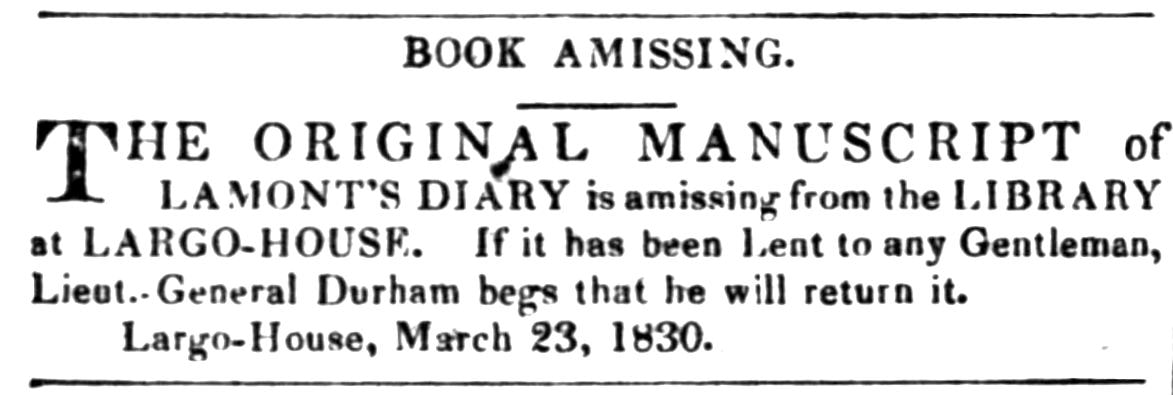

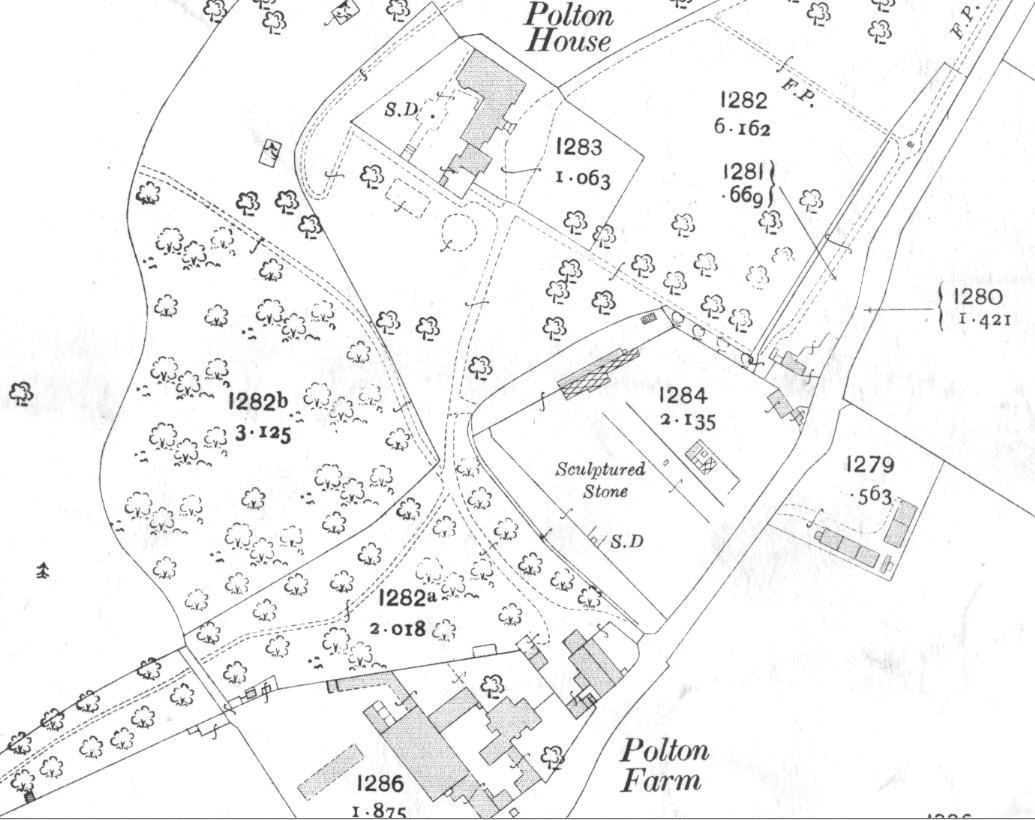

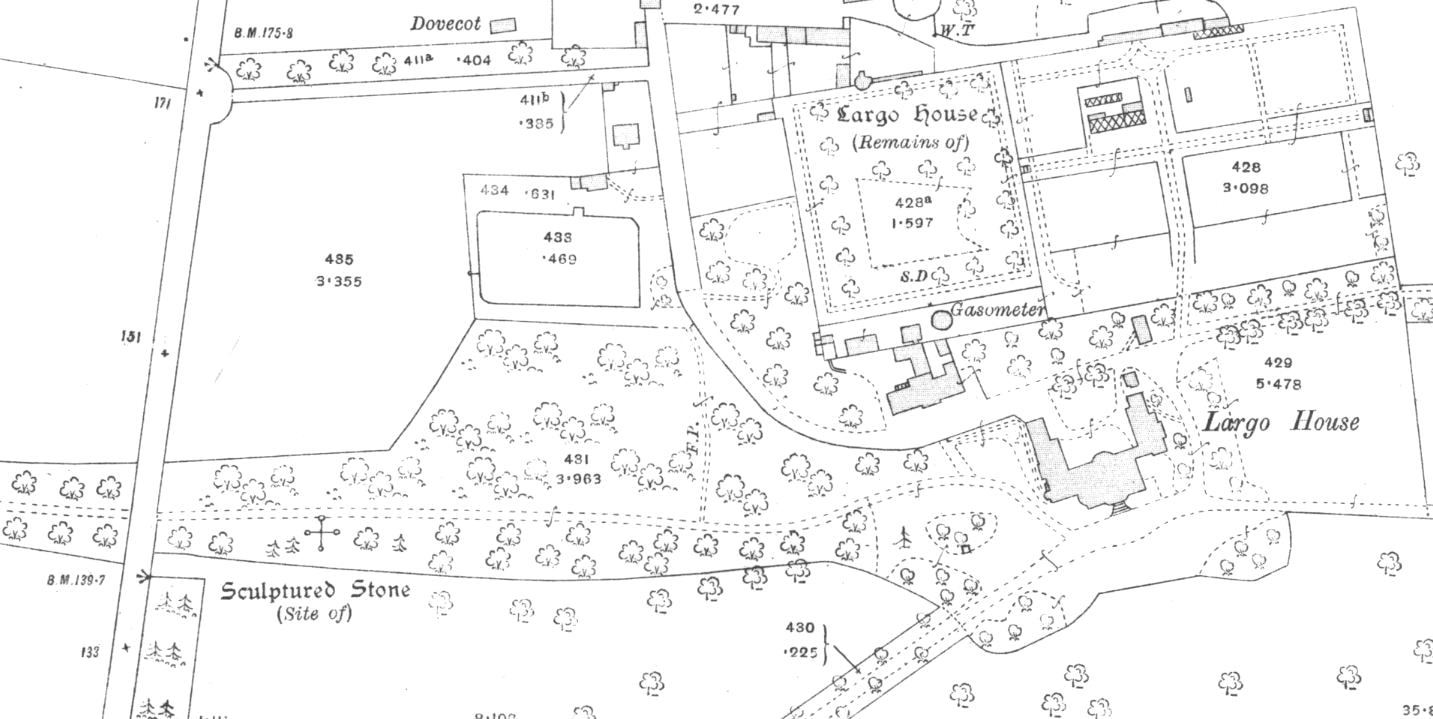

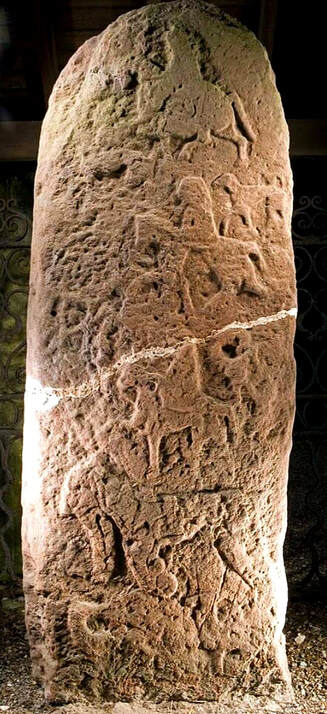

Heraldic visual designs have been used by families, places and organisations for centuries to symbolise their identity. The origins of such designs date back to medieval times when a warrior dressed in a full suit of armour including a helmet would have been entirely anonymous without some visible symbol to identify him. His shield provided a large flat surface upon which to display a pictorial means of identification. A family's arms can evolve through the generations to reflect lines of descent, adoption, alliance, etc. General Durham registered his own coat of arms in 1792 and it carried variations from the arms of his Durham predecessors. It must have been after the death of his father in 1808 that he had his own arms mounted on the frontage of Largo House. Below is an annotated image of it as it appears on the tympanum of Largo House (which being stonework does not reflect colour aspect of the arms).

The full heraldic achievement of General James Durham bears two mottoes: Victoria non praeda (Victory not booty (or loot)) above the crest; and below the arms: Per mare per terras (Through the sea, through the lands).

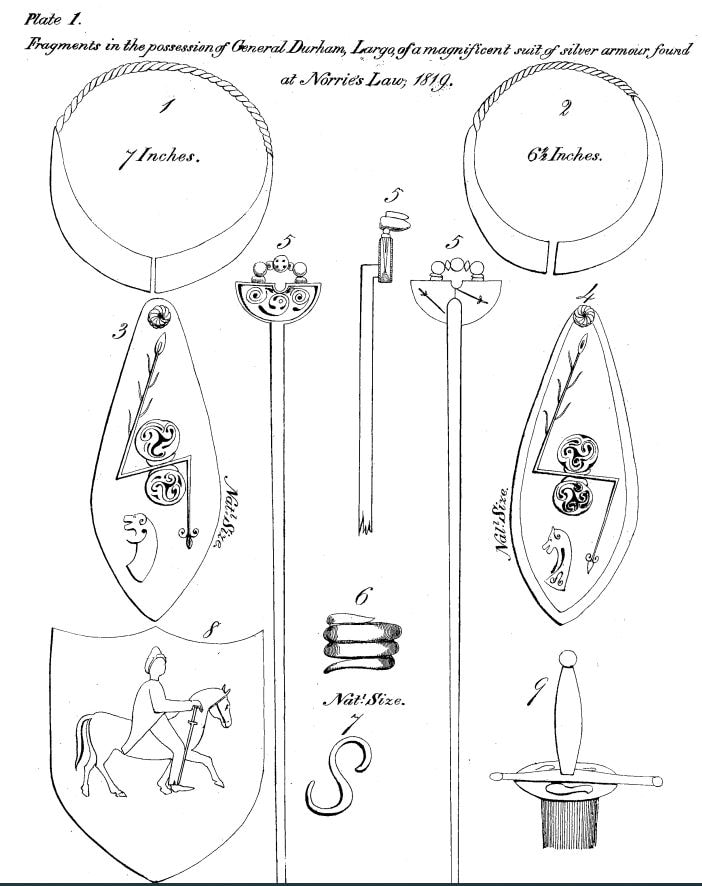

Central to the coat of arms is a shield quartered. Quartering in is a method of joining several different coats of arms together in one shield by dividing the shield into equal parts and placing different coats of arms in each division.

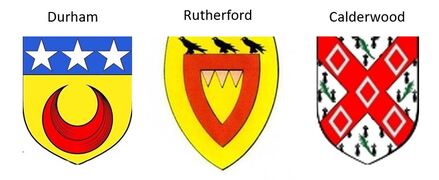

The first and fourth quarters of the shield represent the Durham family (see full Durham shield below) and have a crescent topped with three mullets (stars with straight sides, typically having five or six points - five in this case).

The second quarter bears the Calderwood family shield - a saltire with five mascles (diamond shaped objects) on ermine with palm leaves. This represents the family of General Durham's mother, Anne Calderwood, and is the key variation from his father's arms.

The third quarter reflects the Rutherford family - an orle below three martlets (mythical birds without feet which never roost from the moment of birth until death as they are continuously on the wing). The Rutherford shield, which can be seen below was quartered with the Durham shield when the Rutherford of Hunthill line ended with Margaret Rutherford, wife of General Durham's great grandfather, James Durham.

The quartered shield is flanked by two supporters: horses saddled and bridled. These are known as 'supporters' or 'attendants' which are usually as close to 'rampant' in attitude as possible. Horses represent readiness for all employments for king and country. Above the shield is a dolphin haurient (depicted swimming vertically, typically with the head upwards). In heraldry, the dolphin is an ornamental creature that takes the form of a large fish. It bears little resemblance to the true natural dolphin, which is a marine mammal. A dolphin represents swiftness, diligence, salvation, charity and love. This dolphin sits atop a Baron's coronet (small crown). Such a crown would have six pearls, only four of which are visible on the arms.

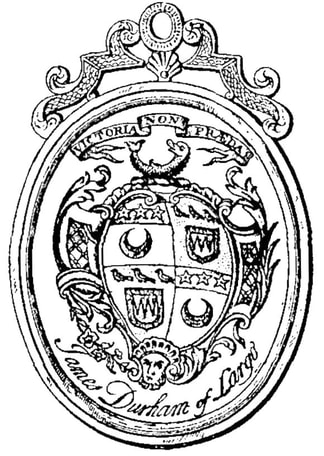

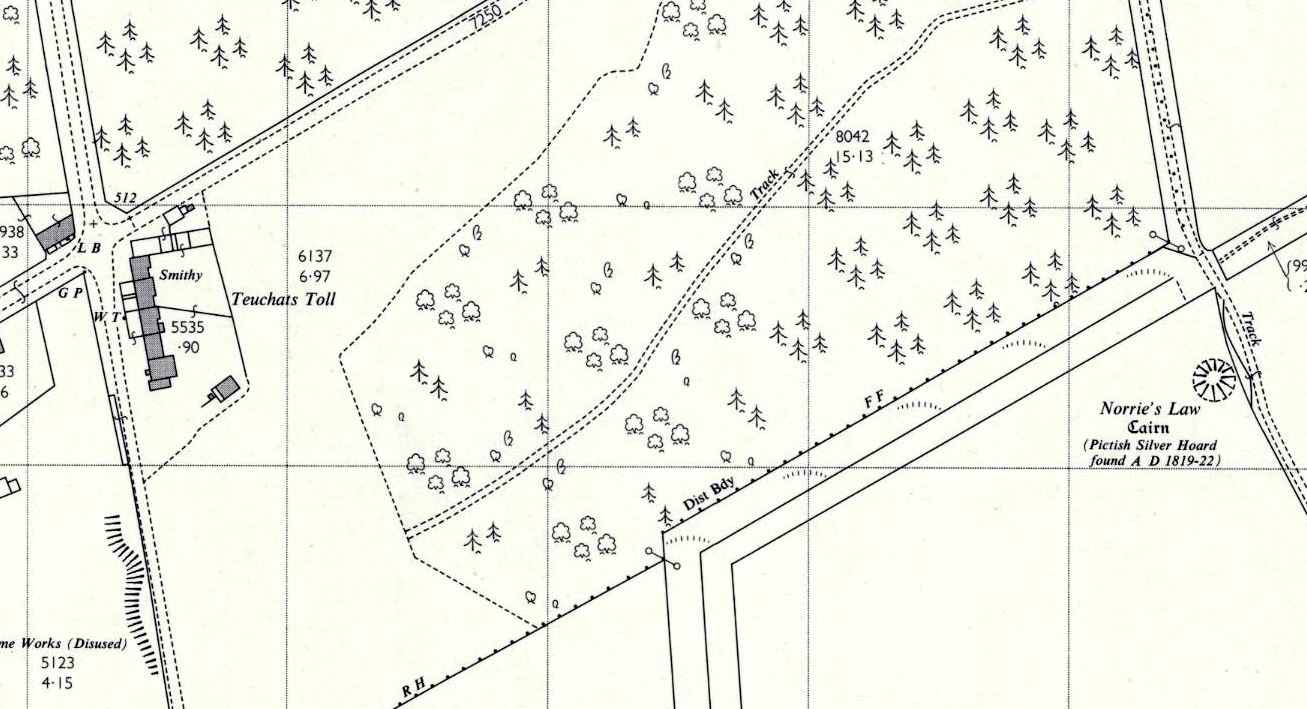

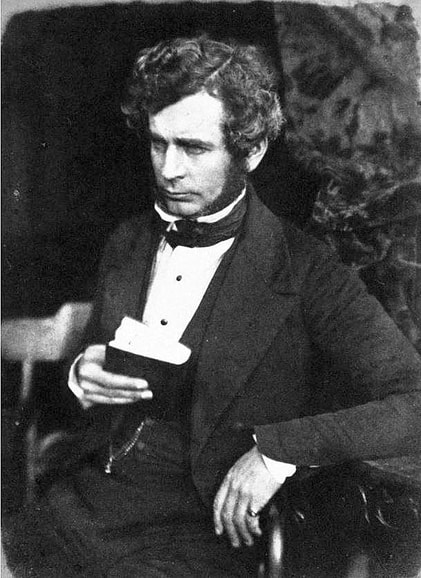

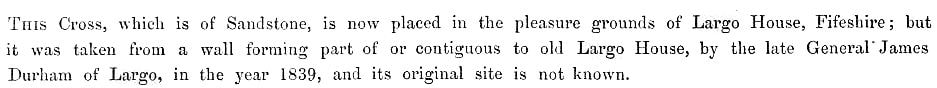

Below is a representation (from a medal) of General Durham's father's coat of arms. Its shield bears only the Durham and Rutherford quarters. This medal, which was awarded to James Durham for archery around 1752, is held at St Andrews University Special Collections and can be viewed on-line in detail here. General Durham's younger brother Philip Charles Henderson Durham had his own coat of arms registered in 1818. The full heraldic achievement featured the same shield layout as his father's (i.e. the one on the medal below) but had different elements added that were more personal to him. More on that some other time.

Despite all the variations in the Durham arms over the centuries, it is the arms of General James Durham (1754-1840) that has been displayed in Largo for around two centuries and can still be seen (albeit obscured by trees) on the tympanum of the ruins of Largo House. As it is difficult to view the ruins today, here is a link to a short drone film over the Largo House ruins from the Vintage Lundin Links and Largo YouTube channel: https://youtu.be/IS6jlq8dPAc

RSS Feed

RSS Feed