By 1891, David Gillies was referred to as a "retired net manufacturer" in the census, residing at Cardy House. David Gillies died in 1923 aged 79. The Cardy Works meanwhile - although pressed into service during both World Wars as an army billet and then a food store - remained suspended in time for decades. For a long time, equipment, furniture, papers, tools, ropes, etc were kept within it as a reminder of the building's industrial past. In more recent years, the Cardy Net Works have been transformed into a modern, beach-side holiday home. Cardy House was itself a Victorian time capsule for many a decade - more on that in the next post.

|

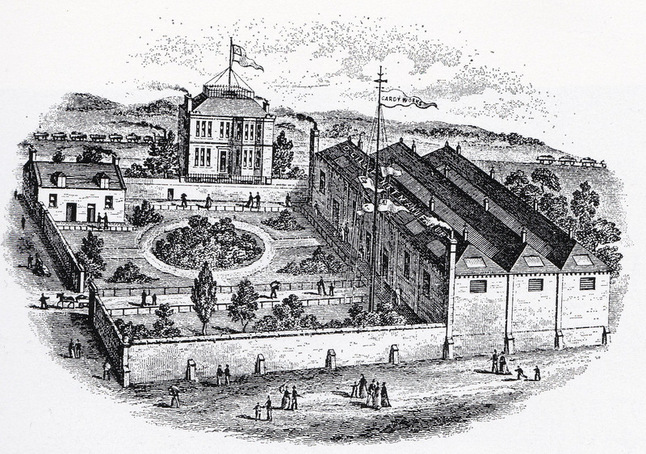

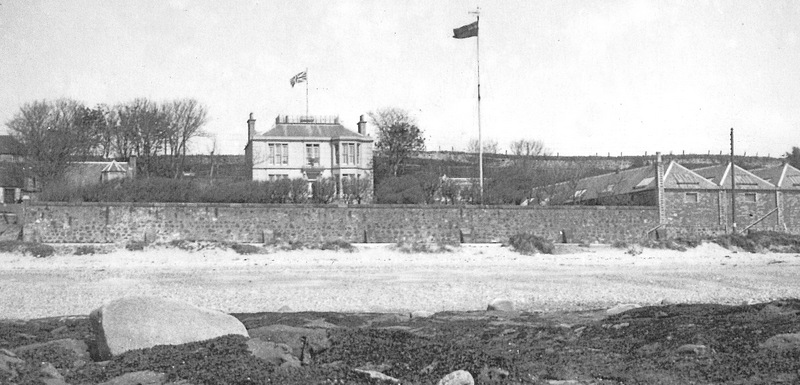

The Cardy Net Works must have become successful very quickly after the business was established, as, by 1871, proprietor David Gillies was able to build himself a substantial villa, which was and still is named 'Cardy House'. The images below show how imposing the house was, on its elevated position behind the works, facing out to sea - especially with the tall flag pole rising from the roof. The artist's impression view of the house and works, used on trade cards, letter heads, price lists, etc, portrays the works as a hive of activity. There are many people visible inside the grounds and on the streets outside. A horse and cart is making its exit through the gates - perhaps rushing an order along to the harbour or train station. Not one, but two, trains are passing along the line behind Cardy House. Flags are flying, smoke is billowing and the gardens are blooming. It's exactly the sort of image that a successful Victorian business would wish to project. The 1885 unveiling of the statue of Alexander Selkirk would not have done business any harm, giving Largo and the Cardy Works publicity and bringing distinguished guests along for the occasion. One of the floral arches which spanned the main street for the event read 'May Cardy Works Flourish'. However, the next year saw the works largely close down (although some elements of the business continued on a much smaller scale). This has been attributed to the decline in herring stocks around the Scottish coasts at that time. Despite a strong desire among locals to see the works return to their former glory after fish stocks recovered, this was not to be.

By 1891, David Gillies was referred to as a "retired net manufacturer" in the census, residing at Cardy House. David Gillies died in 1923 aged 79. The Cardy Works meanwhile - although pressed into service during both World Wars as an army billet and then a food store - remained suspended in time for decades. For a long time, equipment, furniture, papers, tools, ropes, etc were kept within it as a reminder of the building's industrial past. In more recent years, the Cardy Net Works have been transformed into a modern, beach-side holiday home. Cardy House was itself a Victorian time capsule for many a decade - more on that in the next post.

0 Comments

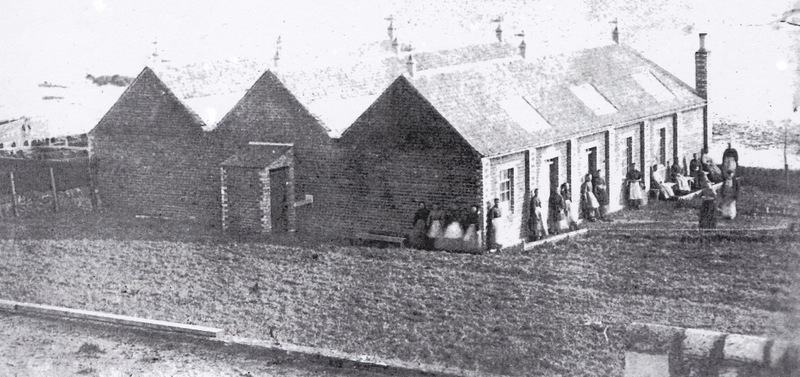

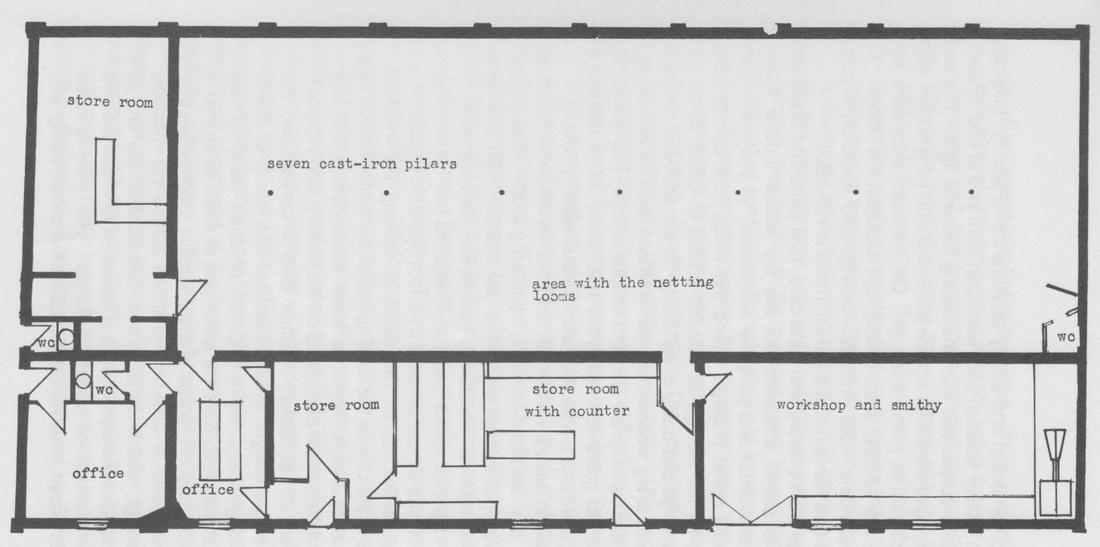

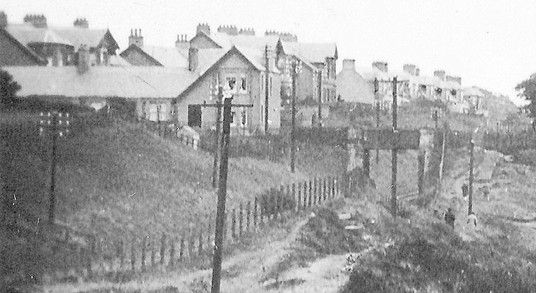

The impending construction of a net works at Lower Largo was announced in 1867 (see previous post) and, by 1871, its founder, David Gillies, was described in the census as a "net manufacturer employing 1 man and 34 women". The image below shows the factory in its original state (prior to an extension being added) which must date to around that time. This grounds are not yet laid out and you can get a sense of what the piece of land would have been like before the net works were built on it - when it was known as 'Cardy Common'. The opening of such a significant source of employment must have been warmly received. Although the work was surely hard, the building was modern and well-ventilated and lit, and the job less messy than many alternatives. The machine operatives were women, who wore dark high-necked buttoned dresses, with white half-aprons, flat dark shoes with toe-caps and had their hair pulled back tightly into buns for safety. The wages book recorded the yardage of net made by each worker every day and at the end of a fortnight (12 working days) the total was divided by 50 (as 50 yards of net was a 'piece'). An experienced worker could make 6 nets in a fortnight. The principle of the machine was to form a sheet-bend by the operative moving a series of levers in sequence. The job was quite a physical one. Employees were reportedly well looked-after. A bowling green was eventually laid out in front of the factory for employee's use during their lunch break. Records show that staff were taken to Edinburgh in 1882 to visit the International Fisheries Exhibition at Waverley Market, where their products would no doubt have been on show. The business flourished and the factory was extended. The 1881 census had recorded David Gillies as "Herring Net Manufacturer employing 65 females and 3 males". The floor plan and photograph below show the extended factory, with a store room, office and W.C.s having been added on the north side, closest to Cardy House. Note that the smithy was at the sea end of the building, where you can still see the chimney today (see image at foot of post). The furnace and bellows are marked on the plan. The gardens have been ornately laid out in the image below, with young trees lining the edge nearest to the factory. To be continued....

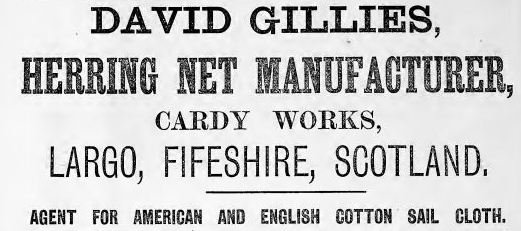

On 28 February 1867 the notice below in the Fife Herald announced that there was a plan to build a net factory at Lower Largo. This enterprise was master minded by 24-year-old Largo-born David Gillies. He had began his career as an apprentice in the office of the firm Messrs Boswell & Co of Leven, spinners and net manufacturers (which later evolved into the Boase Spinning Company). Having left school at 13, Gillies would have had several years experience in the business by 1867. He selected a site next to his former school (located on what is now the Temple car park), known as 'Cardy Common', which had previously been vacant and had been known as a gathering place for tinkers. The ancient name 'Cardy' is thought to come from a name for a blacksmith or tin-worker. David designed the factory building and was supported in the project by his brothers. Constructed of red brick, with a chimney at each end, the works had a three-pitched grey slate roof with many skylights. A large open area would be filled with netting looms and around two sides of the building were store rooms, offices and a workshop and smithy. Gillies had obtained a net making machine from his former employer in Leven and, using that as a template, he made around a further 30 machines in his own workshop. Below is an advert for the business from Worrall's directory of 1877. In the next post, further details of the works and a sense of what it might have been like to work there.

This busy beach scene at Lundin Links, looking towards Drummochy, dates from the 1920s. These people are determined to be by the sea in spite of cool weather - plenty of coats, hats and jumpers are in evidence! Popular activities seem to be sandcastle building and digging deep holes. The group of four children in the foreground are enjoying being captured on camera and have some very sturdy looking spades with them. There are some four-legged friends around too. The railway line, that perhaps brought many of these people to Lundin Links, is noticeable in the top left corner, as is the bridge that took the road over the line. This area of the beach has much more vegetation these days.

The previous post referred to David Russell, who resided at Silverburn and at one time grew flax there which was subsequently sent to the Largo Oil and Cake Mill to be crushed. David Russell (1831-1906) had taken on Silverburn in the Parish of Scoonie (adjoining Largo Parish) in 1854 at the age of 23. He set about redeveloping the property and created a flax mill and retting facilities. Evidence of this can still be seen at the Silverburn Estate today. Above is a view of the flax mill on the left and the workers cottages on the right. The flax retting pond can be seen in the photograph below. Bundles of flax would have been submerged in the water, causing the inner cells to swell, bursting the outer layer, and allowing separation of the fibres from the woody tissue. Bundles would have been weighted down with stones and left for several days. When David Russell realised that the flax industry was on the wane, he took on the old spinning mill at Lower Largo and converted it for seed crushing. In 1874, he moved into paper-making, at the mills at Rothes and Auchmuty, with his Tullis relatives. David married Janet Hutchison in 1868 and they went on to have three sons and four daughters. The beautiful gardens at Silverburn are a legacy of the Russells' interest in botany.

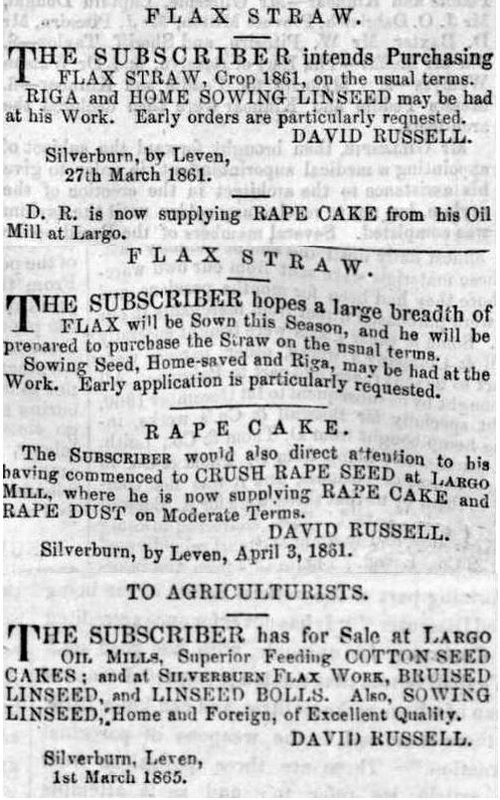

(Source: 'Sir David Russell - A Biography' by Lorn Macintyre (1994)) The previous post covered the latter years of the Spinning Mill at Lower Largo and noted that in 1860, after several years of disuse, the mill premises were advertised for let or sale. Taking up the opportunity the adapt the buildings for a new use, David Russell of Silverburn expanded his business interests to Largo. The story of the conversion of the mill was recorded by David Wallace - a long time employee of Mr Russell. Wallace wrote his memoirs, entitled "59 Years an Old Miller" shortly before his retirement in 1922. In them, he states that he began work with Mr Russell in 1860 (at which time he would have been only 12).... "The mill was driven partly by water and partly by steam. The Cornish boiler was about 18 feet long, with a working pressure of 15 lbs. The engine was the old beam type. Largo was the second oil mill to be operated in the Kingdom of Fife, the Leven Mill...being the first. We had six 4-box presses. Until about 1863 only 10 boxes were worked in each battery. Thereafter, the whole 12 were operated every 12 minutes. With 10 boxes we produced 600 cakes in the spell; with with 12 boxes 720 - this against Hull's output of 440 and 660. The wrappers in the early days were of hair. Some years later wooden wrappers were introduced. We were dissatisfied with those we bought in, consequently we put on our own joiner to make them of greenheart wood, but of a heavier type than was usual in Hull." The comparisons with Hull are made because Hull was a significant centre for oil seed crushing and had 28 seed crushing companies in 1858. It's interesting that the small operation in Largo seems to compare favourably against its equivalents in Hull, where the industry was long-established and widespread. More can be read about the industry in Hull here. Wallace explained that, in the early days, the type of seed crushed at Largo was rape - two kinds, Rubsen and Indian - although they also experimented with other "oddments" such as castor, dodder, ground nuts, niger and hemp. Around 1864, the mill began crushing Egyptian cotton seed "being the first in Scotland to do so". This was imported to Leith or Granton and transshipped over to Largo. The three Fife Herald adverts below - two from 1861 and one from 1865 - bear out David Wallace's account. The memoirs point out that early on the Largo mill refined their crude cotton oil. "I believe it is the case that our little mill, now dismantled of its plant, but still standing, was the first (or at least amongst the first) to produce edible cotton oil in the United Kingdom, and for many years we had a great name for it". The process of refining involved wooden vessels lined with lead. A big wooden wheel, driven by hand, was used to agitate the oil.

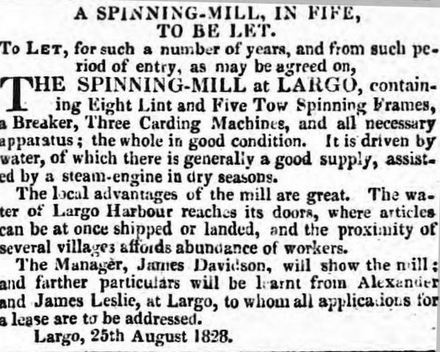

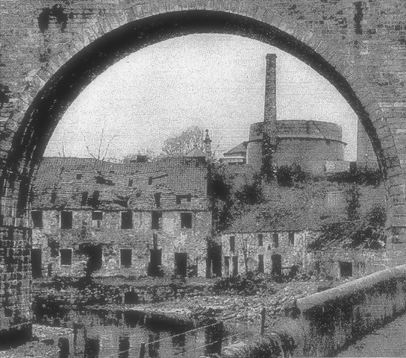

The enterprise at Largo was unique in that, for a time, David Russell grew his own flax at Silverburn, had it threshed, then sent it to Largo to be crushed. This allowed employees such as David Wallace to personally be involved in every step of the process. Wallace said "I myself have pulled, threshed, steeped, dried, and scutched the flax, and have made the seed into oil and cake". The self-sustaining nature of the operation also extended to making their own gas for lighting in the early days, even supplying Largo railway station. Nevertheless, over time, certain facilities were seen as inadequate at Largo and so the Russell firm set up at the old sugar house at the Burntisland docks. Knowledge and staff from Largo moved to Burntisland in 1877 and David Wallace had the honour of making the first cake at the new Burntisland mill, where he would work until 1922. He noted that "throughout my working life I have filled every post in the mill from paring boy to taking sole charge". He recalls that in the early days "the work was much harder and the hours much longer than now". He continues... "I view with disapproval the hashy methods and lack of interest one sees nowadays in many oil mills. In my young days, pressmen, parers, and all, took the utmost pride in their work, and in their machinery. Largo and Burntisland were for many years the best polished-up mills in the country - the press columns always gleamed!" David Wallace passed away in 1927 at the age of 79. When David Russell died in 1906 at the age of 75, the Dundee Courier noted that "he was always on the look out for new methods and new inventions, and spared neither time nor expense to have the business conducted on up-to-date lines." The previous post looked at the beginning and the end of the building which housed the old spinning mill by the viaduct at Lower Largo. Today, an abridged history of its time as an active spinning mill, prior to its conversion into an oil and cake mill. The spinning mill's story can be tracked through intermittent adverts for its let appearing in the newspapers. For example, an 1814 an advertisement in the 14 July Caledonian Mercury read as follows: "The Spinning Mill at Largo, which has a good supply of water, and contains twelve spinning frames, two tow cards, and preparing frames. The mill is conveniently situated near the public roads through Fife, and at the harbour of Largo, where a packet sails to Leith and returns every week." On 8 September 1828 the following advert was published in the Edinburgh Evening Courant: By 1835 the equipment must have been in need of upgrading as an advert that year invited prospective tenants to apply "stating the nature and extent of the improvements required". By the November of that year "the whole machinery in the spinning mill" was advertised for sale. Presumably, the premises were upgraded, as by the 1841 census a Mr David Dand is recorded as the 'Spinning Mill Manager' (and virtually the only resident of Largo Parish who was not born in Fife) and Mr David Leslie as 'Flax Millmaster'. Incidentally, a significant proportion of other adult residents of Largo are described as flax dressers or flax spinners (with many others being home-based hand loom weavers). A year later another advert for the lease of the mill (this time in the Fife Herald of 27 October 1842) read: "The mill contains 918 spindles for spinning flax and tow yarns with the necessary preparing machinery, and other appendages of a going work - all driven by water, assisted by a steam engine of 14 horse-power. The machinery and premises are fitted up with gas - and are well adapted for carrying out an extensive business - being situated close to the village and harbour of Largo, where plenty of workers can be obtained at reasonable rates - and easy access can be had to the flax and yarn markets in Dundee, Kirkcaldy and elsewhere." An insightful description of the buildings and equipment then follows. The water-wheel, steam-engine, driving gear and preparing machinery belong to the landlord and are to be rented with the building. The spinning frames, reels, elevators, turning lathes, heckles, etc, however, were the property of the former tenant and were to be valued. The premises were accompanied by several acres of land, an overseer's house with garden and a "large flax warehouse" at Drummochie. The mill continues to operate into the 1850s, when many would be anticipating the arrival of the railway into the village - not least David Dand, who in 1845 was noted as being a member of the committee of the East of Fife Railway, who in turn were pushing for the line's extension beyond Leven. Ironically, not long before the railway finally made it to Largo in 1857, the spinning mill ceased to operate. The building is advertised for sale or let in 1854 and is billed as being suitable for adaptation into a "woollen, farina, flour or meal mill, a paper mill, bleachfield or for a foundry". However, it appears to have lain empty for a number of years, being advertised again in 1860 as "the premises at Largo formerly occupied as a spinning-mill". Perhaps that could have been the end of the story and the building could have fallen into disrepair. However, a new and innovative future was to come instead. More on that next time.... The flax spinning mill (later an oil and cake mill), alongside the Keil Burn at Lower Largo, was a long-standing feature of the village. However, by the time this photograph was taken in January 1938, it was about to be demolished. Nestling behind the arch of the railway viaduct, even as ruins, the old mill buildings were considered picturesque and this view was one frequently captured by artists. An image of these buildings in a much better state of repair c1890 can be seen on the Canmore website:

http://canmore.org.uk/collection/740625 The Old Statistical Account of 1791-99, states that there were 3 lint mills in Largo Parish and that in Largo "the principal manufacture is weaving". It continues to record that "linens and checks are the great articles. Every weaver, and a good number of others, have their bleaching ground, where they prepare linen" to be sold in Dysart, Kirkcaldy, Cupar and Dundee. A very descriptive advert from 1801 provides a clue to the precise origins of the above spinning mill. Published in the Caledonian Mercury of 3 August that year, the mill was advertised for public roup at the Edinburgh Royal Exchange Coffee-house on 8th September. What was on offer was "the remainder of the lease for 990 years, from Martinmas 1789, of Largo Mills and Grounds" within 100 yards of the harbour and a "similar distance from the manufacturing villages of Largo, Drummochy and Lundinmill, where work people are always to be had at an easy rate, and the greatest part of the old experienced hands may be obtained, a more desirable situation for such a business is hardly to be met with". It continued the specifications as.... "..consisting of about 4 acres of good ground, with a constant supply of water, and a fall of 24 feet. There is at present on the premises a Mill House 40 feet long (besides staircase and wheel shade) by 38 feet wide, lately occupied in spinning flax and tow yarns. The water wheel is an overshot 18 feet in diameter...". The lengthy description points out that on the first floor there were four carding engines, lint and tow preparing frames, turning laith, rest, benches, etc. Upstairs on the second floor there were twelve spinning frames of 36 spindles each, while on the attic storey the reels were stored. In addition to this main building, there were also: a Malts Mill and Thirlage, a Waulk or Plash Mill*, Ware-room, Heckle-house, Wright's Shop, Stable and Byre. Finally, a "dwelling house fit for a manager, situated in Drummochy, with the household furniture therein" was included. Crucially, the advert specifies that "the Mill and Machinery were erected about 2½ years ago" and are "little worse than new". That statement would place the main spinning mill building at a 1798-99 construction date, with its neighbouring smaller buildings probably even older. At any rate, quite an amount of industrial heritage was swept away when the site was cleared in the late 1930s. More on the history of the spinning mill to follow. * A waulk mill or plashing mill was often found alongside a spinning mill. In it cloth was cleaned and thickened. The former police house on Largo Road, Lundin Links was built in the inter-war years and was located opposite the Cottage Tea Room. At the time it was built, county constabularies were organised at a local level and most villages had their own police station or police house, where the local police officer(s) would both live and work. The police house was clearly identified by a sign marked 'POLICE' above the door which could be illuminated at night. A noticeboard was situated in the house's garden. Like the District Nurse, who was located further along Largo Road, the police constable would be well-known in the community and would be ready to be called upon whenever required.

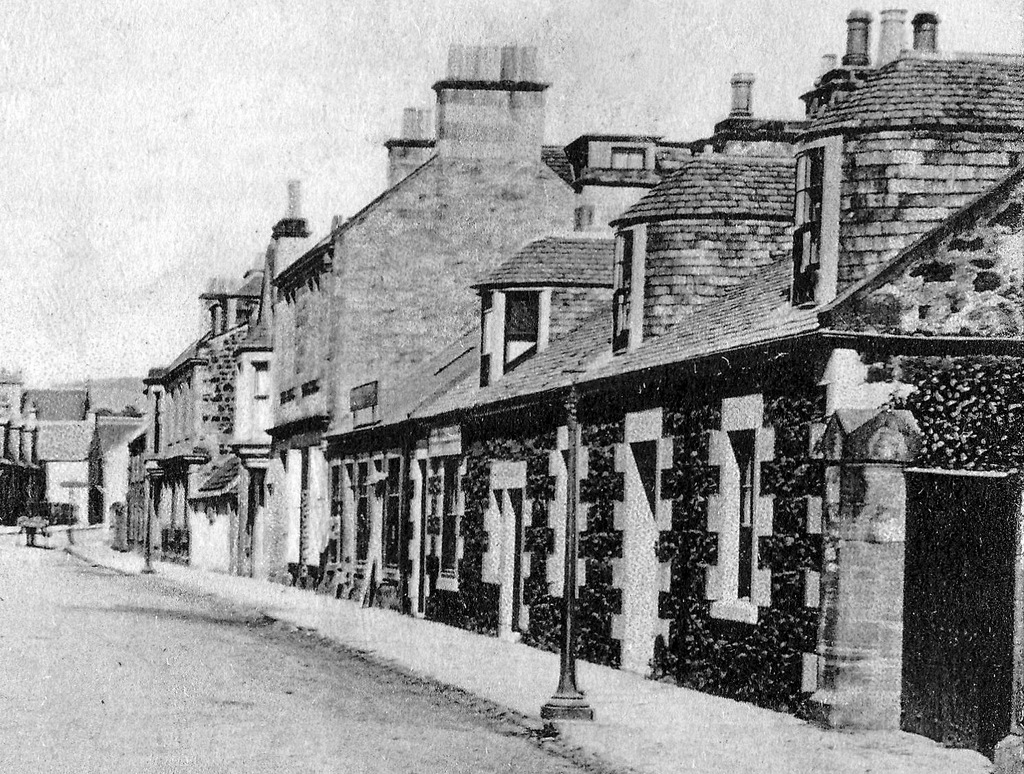

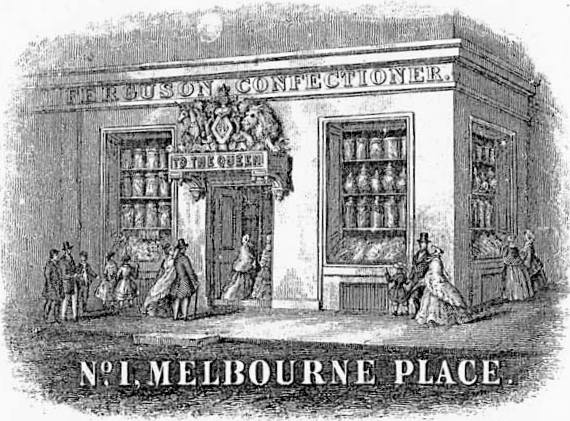

In 1932, Police Constable Andrew Skinner, of 'Lundin Mill Police Station' suffered severe injuries in a cycling accident. The Fife Free Press reported on 9 January that "Constable Skinner was cycling between Pilmuir Farm and Dangerfield, a short distance from Lundin Links, when the front forks of his machine snapped and he was thrown to the ground." He was taken to Wemyss Memorial Hospital with facial injuries. By the late 1980s, the book 'Largo 21' noted that the Lundin Links police beat "is policed by two constables who both reside at and work from the police station in Lundin Links". At that time the Lundin Links/Lower Largo/Upper Largo beat was part of the Anstruther section (having previously been part of a Levenmouth police area). Not long after this, the Lundin Links police station, like so many other village stations closed, and the building became private housing (although retaining the 'POLICE' sign above the door). The era of the police house was effectively ended in 1994 when the government prevented police forces from offering houses as part of remuneration packages. And so, the notion of the village police house, as a place where locals could come to hand in an item of lost property or report some suspicious activity, became a distant memory. George Simpson was the Kirkton of Largo draper and clothier in whose memory the village's Simpson Institute was built. As the Institute was opened 44 years after he died, most people who have subsequently used the facility probably do not know much about the man. There is not much evidence of his business and certainly no photographs of him or of the village at the time he lived and worked there. Nevertheless, some details of his life and legacy can be pieced together. George Simpson appeared in only one census (in 1841), and the information from that record puts his birth at around 1772. Parish records show that he married Helen Mackie of Newburn in Largo in 1800. Their children were Helen (born 1801), Janet (1803), Margaret (1804) and John (1810). George's wife Helen died in 1822 and it would seem that Margaret died at a young age. By the 1841 census George (who is described as 'living on independent means') is found residing with his second daughter Janet in Kirkton of Largo. Meanwhile, eldest child, Helen, is married to a William Wood who is described as a tailor and clothier in consecutive censuses. It is likely that Helen and William took the business over from George Simpson upon his retirement. The business must have been fairly substantial, as in 1851 Wood employed 5 men and in 1861 he employed 4 men and 2 boys. By 1871 Wood had retired, being described as a 'late tailor'. In fact, the 1865 valuation roll also describes him as a 'late clothier' who owns three consecutive properties on Upper Largo's Main Street - one in which he lives and two in which other individuals are carrying out a tailor and clothier business and a drapery business respectively. The shop continued to be a tailor, under different names, for many decades thereafter. The location of the tailor's shop, and of George Simpson's original premises for his business as a draper and clothier, is on the south side of the Main Street, just to the east of the Inn (now the Upper Largo Hotel). The business therefore would have been in the shop on the right side of the photograph below (shown in more detail further below). George Simpson was granted the feu from Major General James Durham of Largo on 1st November 1809. Simpson set up his business at a time of development in the village. The main road had not long been upgraded and the Largo ferry would soon bring new visitors to the area. Over the years, as his drapery business thrived, George Simpson developed other business interests. He had shares in the Leven Gaslight Company, Largo Inn and Granary and in Largo Granary Steelyard at the time of his death. Second daughter Janet (who would go on to bequeath the Simpson Institute) also married a draper and clothier. Her 1841 marriage was to William Galloway whose business was based in Edinburgh. In 1851 Janet and William were at 3 Melbourne Place in Edinburgh, running their business next door to the famous confectioner 'Ferguson', makers of Edinburgh Rock, at No. 1 (see below). The Galloway's subsequently moved to the Newington area of Edinburgh, and their business thrived. So, two of George's daughters remained involved in the drapery trade and after their father's death the two women had a headstone erected in the graveyard of Largo Kirk which reads:

"George Simpson, Clothier of Largo died 27.6.1847 aged 76years. Helen Mackie his spouse died 17.12.1822 aged 52 yrs. Son John Simpson d 19.10.1840 aged 30 years. This stone erected to their memory by their remaining daughters". |

AboutThis blog is about the history of the villages of Lundin Links, Lower Largo and Upper Largo in Fife, Scotland. Comments and contributions from readers are very welcome!

SearchThere is no in-built search facility on this site. To search for content, go to Google and type your search words followed by "lundin weebly". Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed