The Standing Stanes of Lundin are three tall, unsculptured, irregularly shaped pillars of red sandstone. Ranging from about 13'6" to 18' high, they are thought to date back around four thousand years. In a world that's forever changing, the Standing Stones of Lundin provide a reassuring familiarity. These megaliths are one of the few local landmarks that would be recognisable to our ancestors. The land use around the stanes has however changed with the times. Long gone are the sheep pictured in the etching above by local engraver William Ballingall circa 1870. Crops no longer grow around their bases. For the past century plus, golf has been played among and around them.

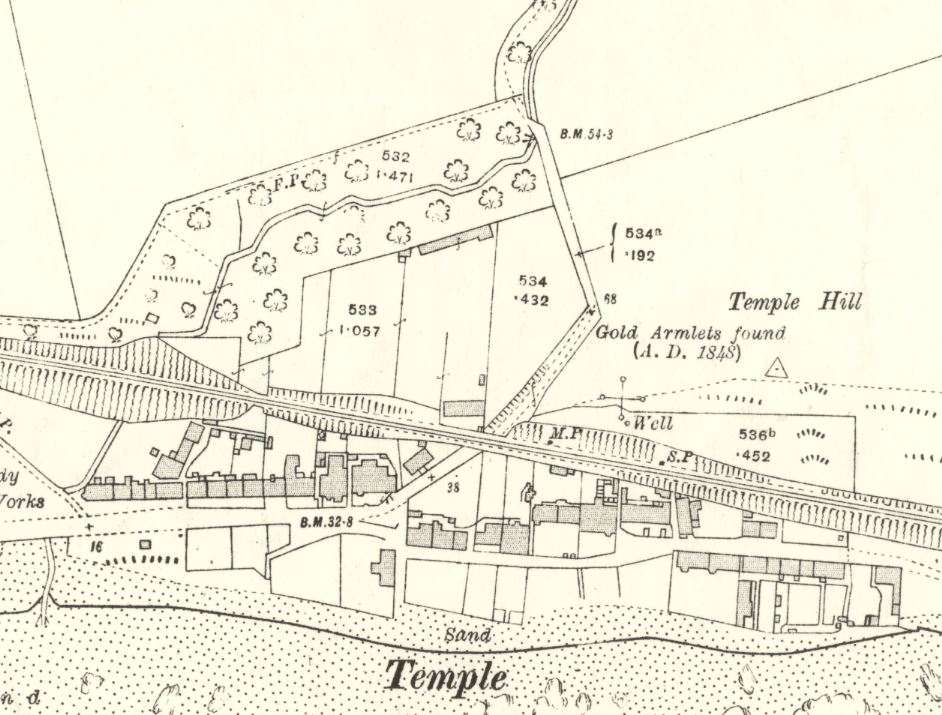

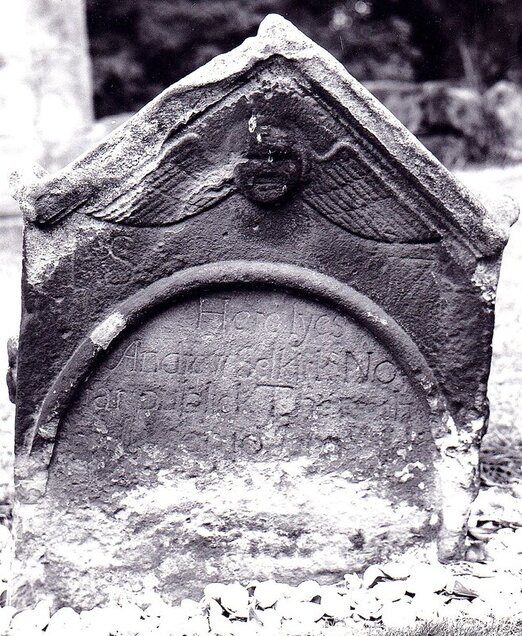

This 1872 photograph by John Patrick shows a gentleman examining the stones while near rows of crops grow at his feet. It was likely a farm worker that discovered a "coffin built of loose slabs" on the site around 1844, which had been exposed immediately adjoining the standing stones.

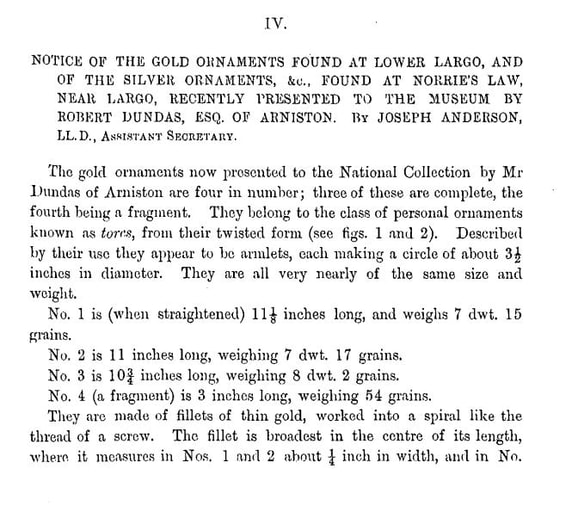

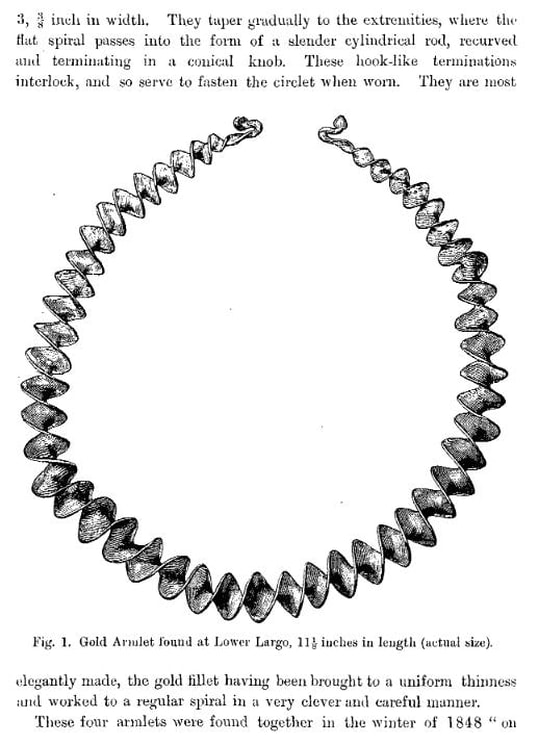

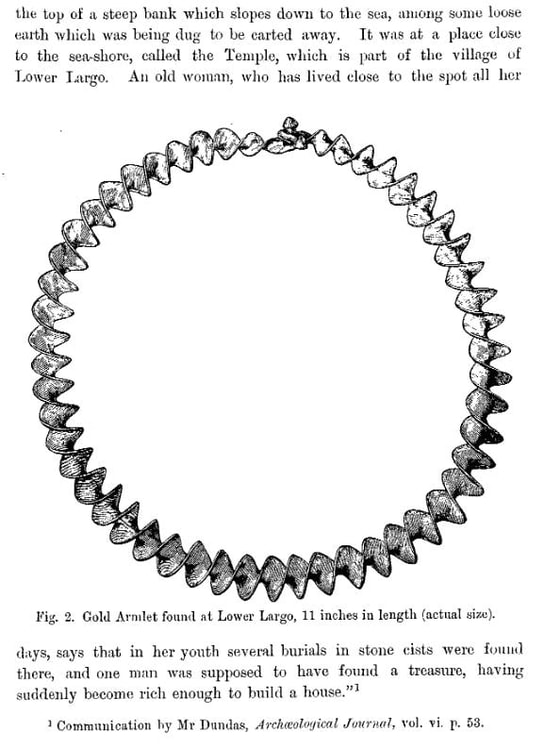

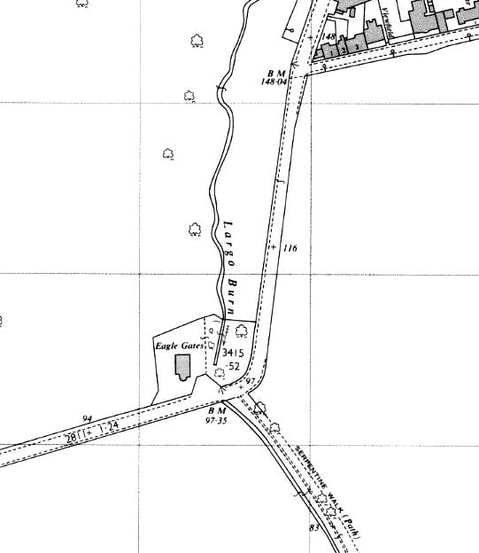

The 1908 image captured by Lady Henrietta Gilmour shows the stones shortly before the Lundin Ladies Golf Club moved to occupy the site and embrace the stanes as a feature of their course. The zoomed in detail below shows clear evidence of graffiti in the form of carved initials and messages. The 2 September 1908 extract from the Leven Advertiser further below explains how this vandalism led to the installation of railings that year.

The initial enclosure was one large railing with a gate (see above). However, having all of the space between the stones fenced off and unplayable for golf must have proved problematic. In 1922 this was replaced by two sets of railings forming separate enclosures. Golfers could then play through the middle of the stones as part of the course's second hole. These railings (shown below) remained in place until the early 1980s.

The newspaper piece below from a 1969 East Fife Mail shows a section of the railings. By this time they were looking a little buckled and worse for wear.

The two images below, both from the Canmore Collection, show the stanes shortly before and after the railing removal. The first is from the mid-1970s and shows a wider scene of the second hole fairway (and third tee behind) with the railings still around the stanes. The second image dates to 1986, when the stanes had been recently released from their iron enclosures, enabling people to fully enjoy their ancient splendour from all angles.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed